The Consequences of America’s Debt

I’ve warned about America’s increasing debt load for many years now.

While U.S. debt has been on a gradual increase for decades, it was only after the Great Recession in 2008/2009 that we saw the debt levels really begin to increase.

As you can see by the graph above – courtesy of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank’s Economic Research Division (FRED) – the upward trajectory of the U.S. debt steepened in Q3 of 2008 (click the graph to be taken to the interactive web page version).

And its rise has continued since, taking an unprecedented jump in Q1 of 2020 as a result of federal efforts to mitigate the financial damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic and governments’ reactions to it.

To put actual numbers to the graph above, the beginning of 2008 saw America’s debt levels at $9.4 trillion.

At the end of 2019, U.S. debt totaled $23.2 trillion.

And currently, our debt is hovering around $27 trillion.

With Congress considering a $1.9 trillion Covid Relief/Stimulus bill for which no commensurate revenue is provided, that amount would be added to the $27 trillion amount boosting our debt load that much higher.

What Do Those Numbers Even Mean

If you’re like most Americans, I might have just as well written an unknown foreign language in place of those trillion dollar numbers.

What does $9 trillion or $27 trillion even mean?

One way to put the debt numbers into context is to consider them next to the amount it takes annually to operate the entire U.S. government.

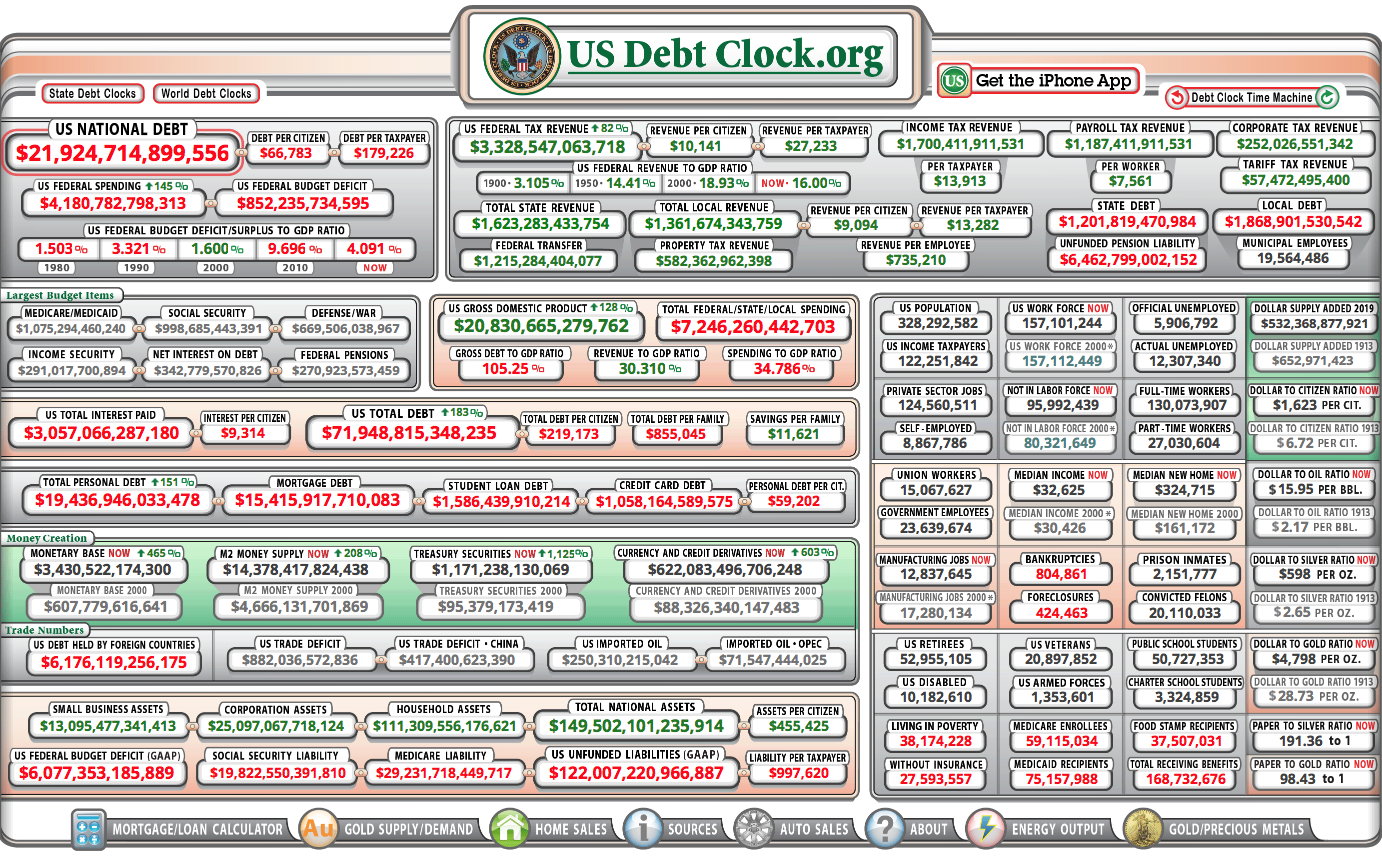

In our piece “Why Saving Now is More Important Than Ever Before,” we note the federal operating budget for fiscal year 2018 was $4.1 trillion.

While the amount of money that was collected by the U.S. government (taxes, fees, etc.) was $3.3 trillion.

So, as you can see, the U.S. debt is roughly 6 times higher than the amount it takes to operate all aspects of the federal government each and every year.

While this is an illustration of what the debt levels mean, it’s not the best way to consider debt levels and their potential effect on an economy.

Most economists view debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), or the total value of all goods and services produced by a country, as a barometer of its seriousness.

As a percentage, when debt-to-GDP hits the upper 70% to 80% range, concerns begin to be raised.

America’s debt-to-GDP percentage hit 102% in 2020.

And America’s elected leaders show no signs of taking U.S. debt levels seriously any time soon.

In fact, in addition to the $1.9 trillion Covid relief/stimulus bill, it is likely we’ll see other significantly priced legislative initiatives over the next year or two.

Once again, adding even more to the U.S. debt.

The Consequences of America’s Debt

So, why is it a big deal that America has a large amount of debt? Why should we care?

To put it succinctly, large amounts of debt, such as we’re seeing now in the U.S., typically result in lower economic growth.

And lower economic growth equates to fewer jobs being created, lower numbers of businesses being started, incomes that remain stagnant or decrease and a variety of other negative factors.

Bottom line, the standard of living for all Americans will suffer.

But when will the debt become a concern?

This is part of the problem with debt from a governmental standpoint, and why so few likely take it seriously.

There’s a saying when it comes to governmental debt and its consequences: “It’s not a problem…until it is.”

And, unfortunately, once the “until it is” aspect hits, it’s too late to do anything substantive to correct the problem.

You’ve just got to ride the negative aspects out and hope things turn for the better quickly.

Thus, most elected leaders ignore the problem since the “until it is” part is viewed as something far off in the future, not their issue to bother with.

While a lower-growth economy is the bigger picture result of large debt loads, these are the more focused consequences for which the U.S. needs to watch going forward.

If these begin to appear in the U.S. economy, it’s possible the “until it is” part has begun.

- Inflation

- Hyperinflation

- Loss of Reserve Currency Status

Inflation

Inflation is the rise of prices of various goods and services within an economy, resulting in the decline of purchasing power.

We haven’t seen significant, widespread, inflation in the U.S. for many years.

As you can see from the graph above, again courtesy of FRED, the U.S. inflation rate has remained below 2%, for the most part, since 2009.

And prices for most goods and services have remained flat or even declined over those years.

A few exceptions stand out, though, such as health care, higher education and except just after the 2008 crash, housing prices.

If we would begin to see widespread, significant, inflation going forward, our debt could very well be the cause.

When pricing rises for groceries, household staples, gasoline, utilities, everything, really, it reduces the amount of disposable income individuals and families have available. Thus lowering the standard of living.

Small pricing increases can be a positive in that businesses make more money and hopefully pass some along to employees in the form of cost-of-living pay increases.

Large increases, however, are not good for the overall economy, and can lead to significant financial pain for individuals and the economy.

And continued inflation can get out of control leading to hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation

The term hyperinflation may conjure the image, from your high school history books, of a man pushing a wheelbarrow full of bills down a city street.

This played out during the early 1920s in Germany when the Weimar Republic accrued massive war debts and exacerbated the problem by printing money without any economic resources to back it.

Hyperinflation ensued and that wheelbarrow of German Papeirmarks was sufficient to only buy a newspaper.

Hyperinflation is an economy killer.

An example might be a loaf of bread whose current $3 price jumps to $10, $20, or much more, in a period of months. With no increased income to cover the increased cost.

Think of such price increases spread across all aspects of the economy.

Aside from a very few, no one could afford to live. The consequences would be dire.

And, hyperinflation can appear with limited warning. It might be preceeded by a period of gradual inflation, or it might hit all at once.

Again, the potential result of extremely high debt levels that lead to decreased confidence in the economic and monetary system.

Loss of Reserve Currency Status

And it’s this decreased confidence in the U.S. economic and monetary system that poses the biggest threat.

Right now, the U.S. is able to maintain a relatively stable economy by virtue of the dollar being viewed as the world’s reserve currency.

Since 1944, the U.S. dollar has been the primary reserve currency used by other countries.

It’s this status that allows the U.S. to issue such large amounts of debt and use the resulting revenue to fund spending initiatives it otherwise could not afford.

Foreign countries and other investors from around the world invest in U.S. debt because of its reserve currency status and the viewpoint that it is one of the most stable and liquid forms of exchange.

Should that impression change…possibly due to significantly large debt loads or perceived currency or government instability…the reserve currency status could be shifted to another currency, resulting in a loss of interest in U.S. Treasuries.

Make no mistake, China would love to take the reserve currency status from the U.S. as it positions itself as the world’s leading economy.

Once the reserve currency status is lost, U.S. debt becomes much less attractive and America’s ability to fund its outsized spending is diminished.

And with it, so too is the economic growth to which we’ve become so accustomed.

There are other potential consequences to carrying such large amounts of debt, such as; stagflation, increased interest rates, increased interest payments that crowd out other federal spending, and the lessened ability to respond to future financial emergencies, to name a few.

None of these are positive, and some could have cataclysmic results not only as they relate to the U.S. economy as a whole, but to individual Americans and their families.

Modern Monetary Theory

In all fairness, I need to offer an alternate view to what’s been presented above.

There is an economic theory that has been around for a while now but has become more “in vogue” in the past few years titled Modern Monetary Theory.

The theory basically states that debt is not a concern and should not be a constraint to government spending.

Personally, I disagree with the view and its advocates’ support for deficit spending.

However, an argument can be made that we’re already testing the theory – and will do so even more in the coming years – by virtue of America’s current monetary situation.

If you want to learn more about MMT, a Google search will provide a variety of pro and con articles on the topic.

The End Result

If Modern Monetary Theorists turn out to be right, America has nothing to worry about with regard to its increasing debt levels.

I hope that’s the case.

Because, otherwise, there will be a day of reconing, and it won’t be an easy process to get through.

Both the country, and individual Americans, will face financial hardships and conditions that have never been experienced before.

And the road back to normal will be long and difficult.

On the one hand, it’s surprising that our elected leaders continue to disregard these consequences while pursuing financial endeavors beyond the country’s means. On the other, it’s not.

We’ve witnessed over this pandemic that many of our elected officials care more about themselves and political gameplay than they do about the citizens they represent. And the country they serve.

So it’s not that surprising that they continue to spend, building debt levels that will surely result in negative consequences for us all.

It’s a shame. But that’s where we are. Let’s hope for the best, but prepare for the worst as U.S. debt levels continue to grow.